Exploring a River through Art

paintings, pastels, drawings, monotypes

This is the brochure I created for my solo show (of the same name) at the Arts Society of Kingston, December 2019. To see more of the work I created for this project, please go to the Landscape tab in my website.

The Journey Begins...

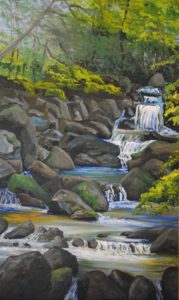

The 19.5-mile long Sawkill Creek cascades down from the northern slopes of Overlook Mountain, over 2000 ft above sea level, to the level plains bordering the Hudson, merging with the Esopus along Kingston’s west flank.

The Sawkill moves from an idyllic environment in the mountains of the Indian Head Wilderness area to the brute force of the ever present modern day world at its end, with Interstate 87 interrupting its bucolic flow into the Esopus. This river, I discovered, holds the past, present, and future.

I decided to focus on the Sawkill because it is always present in my life with Woodstock. My first visit to the village was dinner at the Bear Café, beside the creek. The first house I lived in here was almost next to the river… The river runs through Woodstock and surrounding countryside like a leitmotif in a symphony: ever present, reappearing at unexpected turns.

What I didn’t expect to see was how the river connects the area. It helps boost the tourist industry which flocks to the Woodstock region. Woodstock School of Art regularly has its instructors and students on its banks for plein air painting. Some of its waters are kyaked, others are fished, and there is the Big Deep watering hole. And of course, a steady stream of hikers walk up to Overlook Peak, with the hardier souls continuing on to the silence of Echo Lake, where the Sawkill is born.

A River of Constant Change

The Sawkill evolves. Even Echo Lake has changed since my last visit, 10 years ago. There are more people—you can camp there now—and more homesteads, of the beaver kind. The first five miles or so (2.5 miles as the crow flies) is in wilderness area, with no footpaths or guidelines. I hired a professional guide and we did it the hard way, going uphill instead of down. It’s not a journey for the faint of heart because the new growth forest has deposited layers of fallen leaves hiding steep ravines and sharp rocks, while the storms of climate change have clogged many waterways with fallen trees.

The wilderness area opens out into the old farmsteads of Shady, many of which can trace their ancestry back to the early 18th century. Most original settlers were forced to be tenants on what were essentially feudal lands. Their families farmed the land for generations, but didn’t get full rights of ownership until the early/mid 1800s when they rose up against abusive absentee landlords and won!

Welcome the Industrial Revolution

The Sawkill trips and skips down into Bearsville, named after Christian Baehr, who set up a general store by the river in 1839 to service the developing tanning industry. For while the farmers in the hills were fighting for their rights, the small hamlets downstream – Woodstock, Zena, Sawkill—were barreling into the 19th century industrial age.

Tanneries, smelly and environmentally toxic, proliferated because of the fresh water and hemlock forests. Tannery Brook, a Sawkill tributary running through Woodstock, maintains through its name a memory of this business. Two glass making factories set up shop, one giving Glasco Turnpike its name. But the most prevalent industry of the time was mining for blue stone. Witness the old California (on Overlook Mountain), Onteora, and Jockey Hill mines.

The numerous waterfalls and rapids spouted mills of various kinds, often within a mile or two of each other, as with the Woodstock sawmill, where the golf course now spreads, and the old sawmill off Zena Road, whose buildings still stand.

Given today’s environmental and social sensibilities I wonder how attractive we would have found this area back then, despite the upper class tourist industry that flourished in the high mountains.

Enter the world of Art…

But again things changed. Many of these industries were dying or gone by the early 20th century. 1902 saw the birth Woodstock’s extraordinary history of becoming the American artist colony of the century (and still going strong). It was on the peak of Overlook Mountain that Bolton Brown decided this was the place to set up Byrdcliffe, the founding arts colony. Did he see Echo Lake, and the Sawkill Creek?

Certainly it seems that one very famous American artist of the past did—Thomas Cole. I’ve been told that, toward the end of his life, he hiked up Overlook Mountain via the Sawkill (in today’s wilderness area) with the original MacDaniel of MacDaniel Farm. If this is true, it gives my hike along the river to Echo Lake special meaning.

…and Water

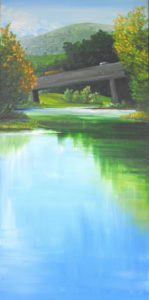

Continuing downstream from Woodstock, the Sawkill is dammed in several places to form reservoirs for Kingston. These artificial lakes add a quiet reflective beauty to the area in addition to feeding a thirsty town. The land spreading out from the river along Zena and Sawkill Roads lead into the Esopus valley, which has the best farmland in the region.

Where the Sawkill merges with the Esopus, in that fertile valley, the expected silence of a very bucolic scene is ripped apart by the raw noise of traffic on Interstate 87, running from New York City to the Canadian border. Our modern industrial world still abuses this river.

Yet those small reservoirs off Zena give me pause. In the 21st century Kingston is now becoming a center for the arts… First Woodstock, now Kingston. Could it be something in the (Sawkill) water?

Last but certainly not least: THANK YOU to all the people who helped make this project come to fruition. Local farmers and home owners, who didn't know me from Adam, let me paint, draw and photograph the river from their fields and backyards. Local historians gave me information I certainly would not have found elsewhere. As some wish to remain anonymous, I'm not naming anyone here, but my heartfelt appreciation goes to all of you who helped me in this.

© Linda Lynton, 2019